YouGov has released its first UK-wide MRP since the 2019 election. Like all UK polls in the past two years, it shows a substantial Labour victory. However, with YouGov’s strong track record of UK MRP, the results have created a splash with politicos. While most commentators focussed on the magnitude of Labour’s victory (a 120 seat majority), some have pointed out that the model’s implied voting intention is not so catastrophic for the Government. Indeed, the estimated 13.5% lead is much smaller than YouGov’s other public polls, which have ranged between 19 and 24%. This disparity raises important questions about polling in general in the lead up to the next election.

YouGov’s Patrick English explained on Twitter that the difference can be explained by the pollster’s MRP methodology. Rather than modelling “Don’t Know” as a separate option, YouGov’s approach is to remove them from the sample when modelling, implicitly assuming that those saying “Don’t Know” now will end up voting in the same way as those with a similar demographic/political profile. While more complex, this applies a similar logic to the approach taken by Opinium in their regular polling – weighting the sample after removing Don’t Know, rather than before.

This has such a significant impact on voting intention because “Don’t Know” is not drawn evenly from across the population. A majority of undecided voters in the last election ultimately voted Conservative and supported Leave in the EU Referendum In the most recent wave of the British Election Study, for example, undecided voters were 59% Leave-voting (excl. non-voters), compared to 50% nationwide. Similarly, they voted 58% Conservative in 2019, compared to 44% nationwide.

If undecided voters are removed from the poll at the end of the process, as most pollsters currently do, a significant chunk of the Conservative and Leave vote is effectively removed from the sample. In the past, this has been justified by saying that “Don’t Know” is akin to abstaining – but the majority of undecided voters currently say that they intend to vote. By contrast, the MRP/Opinium approach applies the weighting after removing undecided voters. This effectively up-weights 2019 Conservatives and 2016 Leave voters who gave a voting intention, in place of those who said Don’t Know.

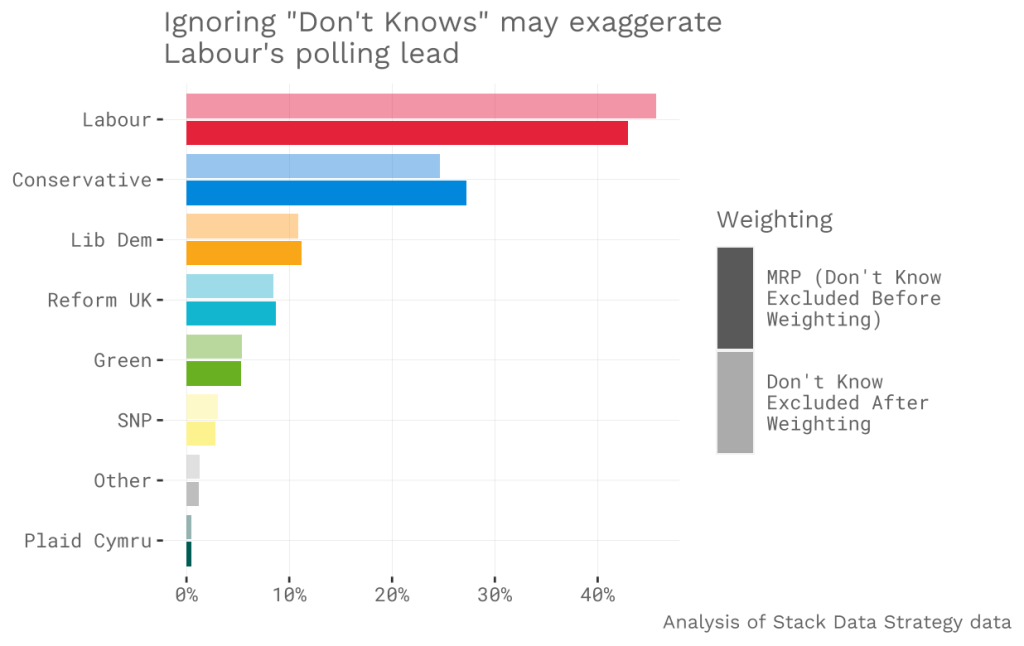

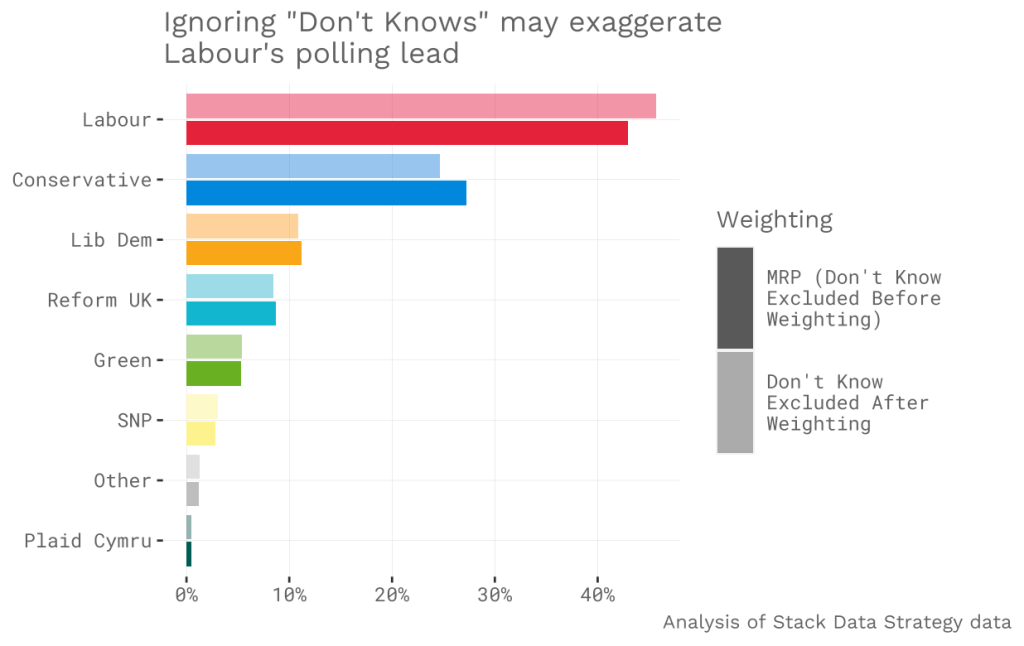

Clearly, the effect of this is substantial. When Opinium switched methodology, they released the same survey by both methods for comparison – finding that weighting after removing “Don’t Know” increased the Conservative voting intention by 2% and decreased Labour’s by 5%. This likely explains a large proportion of the difference between YouGov’s MRP (Con 26%, Lab 40%) and public polls (~Con 23%, Lab 44%).

I am fortunate enough to be able to compare both methods with Stack Data Strategy’s data. Using the same sample, weighting before excluding “Don’t Know” produces Con 25%, Lab 46%. Weighting after excluding Don’t Know gives Con 27%, Lab 43%. Although the difference for each party is relatively small, the swing between Labour and Conservative here is large enough to have a very substantial impact on the number of seats won – the difference between a total Conservative wipeout and a moderate Labour majority.

The question this poses is whether all pollsters should be weighting their data after having removed those who selected “Don’t Know”. So far, this blog has been favourable to that argument. For balance, it is also worth highlighting the two arguments which I think are reasonably persuasive in favour of weighting before removing “Don’t Know”.

The first is a matter of principle. A section of the public would select “Don’t Know” if asked today, so the poll should be weighted to reflect this. By weighting after having removed “Don’t Know”, you are making assumptions about undecided voters. Rather than being a barometer, the poll becomes an election model. If we accept this argument, my view would be that all polls should be published to include the “Don’t Know” number. Typically, headline numbers remove “Don’t Know” at some point in any case – allowing for comparison with election behaviour. While it may not be on the ballot paper, people who selected “Don’t Know” are still reflecting their ‘real’ indecision at this time, which should not be discounted in opinion polling.

The second is that undecided voters may not vote in the same way as those with similar demographic profiles. By removing “Don’t Know”, assumptions are made about undecided voters. In practice, by weighting before removing “Don’t Know”, you assume that undecided voters will vote in the same way as the rest of the sample as a whole. In this view, undecided voters are truly undecided – a coin toss away from voting for any other party (in proportion to their overall VI). Meanwhile, if you weight after removing “Don’t Know”, you are assuming that undecided voters will revert to the same demographic patterns as those who did give a preference. By nature, though, undecided voters are, in fact, different. There is a reason that they selected “Don’t Know” above any other option (often still selecting “Don’t Know” even when pushed by a follow-up question). That in and of itself implies that they constitute a distinct sub-demographic, and may exhibit entirely different voting behaviours when they are faced with the final voting decision.

Predictably, I think the answer is probably somewhere between the two. Undecided voters are different to those who give a preference, so we shouldn’t assume their demographics are deterministic. But it would be wrong to assume that 59% Leave, 58% Con19 undecided voters are evenly undecided between all parties. By removing undecideds after weighting, a majority of public polls (according to Patrick Flynn’s pollster methodology comparison) have Remain and Labour-skewed samples. This creates a serious risk that polls will be biassed against the Conservatives in the run-up to the next election.

Leave a reply to La reforma en el Reino Unido aumenta los índices de popularidad en las encuestas, pero ¿son reales sus partidarios? – Espanol News Cancel reply