In October, voters in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén’s 6th district voted in an interim election to replace Fidesz MP Ferenc Koncz, who had died in a motorcycle accident in July. With Fidesz’s two-thirds majority at stake, the by-election became an important test for the opposition’s ability to turn out voters. In 2018, Fidesz did not win a majority of voters in the district (around 49%), so the hope was that a joint opposition candidate could win in a two-horse race. Instead, Fidesz won with an increased share of the vote (51%) while the opposition won 46%.

This interim election shows one of the key weaknesses of the opposition going into the 2022 elections. Although opposition parties can usually rely on narrow majority support from voters between them, in opinion polls, the reality of turning out these voters for joint candidates is much harder. The opposition candidate in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén, for example, had been the Jobbik candidate in 2018 and was revealed to have made anti-semitic and racist comments. While he was clearly a weak candidate, that the opposition failed to turn out voters in this interim election may show the difficulties of winning single-member districts, even with joint opposition candidates.

This problem is, of course, by design. The electoral system passed by Fidesz in 2011, through its complicated tier system, penalises fragmentation and increases the importance of single-member districts. These districts are skewed, so that there are a small number of very liberal, left-leaning districts – mostly in Budapest – while the vast majority of other districts have comfortable Fidesz majorities. The electoral system has rewarded Fidesz’s strategy of swinging to the right, devouring the Jobbik base and leaving the liberal opposition to squabble over central Budapest. The only strategy open to the opposition is to run joint candidates and a joint list – as they plan to in 2022.

The centrality of single-member districts in the new electoral system increases the importance of political geography, which is why I was pleased to see that the interim election results were posted on a precinct level (as they usually are) including a map of each precinct (which is new). Precinct level election results – if rolled out to every district – could be key to better understanding voting patterns and potentially spotting cases of gerrymandering.

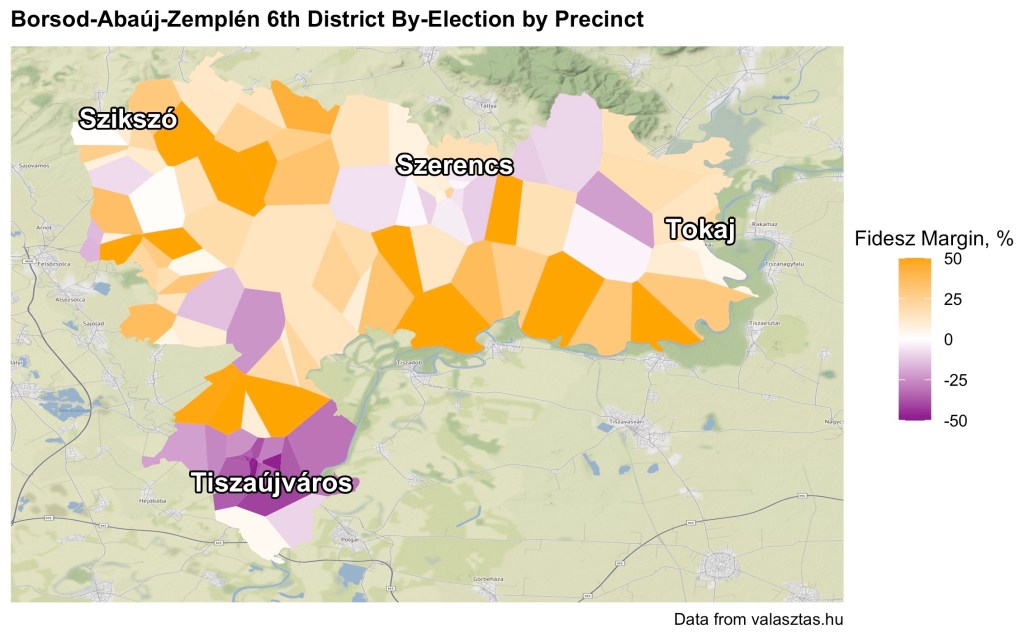

Mapping Hungarian election results by precinct has been done before (and possibly elsewhere that I have not seen) but the lack of precinct geography data makes the process slow and imprecise. In this case, precincts were shown on Google maps, from which I could scrape latitude and longitude data. Unfortunately, this data was not perfect, as can be seen in this first map.

The precincts do not cover all urbanised areas, they are overlapping in places, and in some cases they have very questionable boundaries. Still, we can already begin to see the broad voting patterns. Tiszaújváros, in the south of the district, voted overwhelmingly for the opposition, in many areas by over 50%. This is the largest town in the district, so makes up a large proportion of the opposition vote share. Meanwhile, the other towns – Szerencs, Tokaj and Szikszó – were more evenly split, while rural areas went heavily for Fidesz (some by upwards of 70%).

This is mostly consistent with what I expected. While Jobbik previously performed well in rural areas, the new joint opposition is mostly confined to towns, which tend to be more educated and younger (although I haven’t looked at census data below district-level for this blog post). Fidesz has maxed out its support in rural communities that tend to be overrepresented in the new electoral system. In this case, for example, the district is very efficient for Fidesz, with rural areas neutralising more liberal towns – a pattern which is seen across the country.

To get a better look at these patterns, and to solve the problems of overlapping precincts (i.e. to make the map look prettier) I use a Voronoi diagram based on the centroids of the precincts used above. The Voronoi diagram means that the whole area of the district is coloured according to its nearest centroid, creating a much more visually pleasing image and allowing the patterns to be parsed instantly.

Again, we can see opposition support concentrated in Tiszaújváros while rural areas are much more pro-Fidesz. However, this is not a particularly accurate representation of the precincts, which generally have similar locations but dramatically different shapes, especially in the largely uninhabited areas in the northern portion of the district. And, obviously, it’s important to remember that land doesn’t vote.

To better represent the voters of the district, I used David Zumbach’s very helpful R script to produce an animated comparison of precinct results, with circles approximately proportional in size to the number of voters, similar to his map of Swiss referendum results.

In Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén’s 6th district, a large number of votes were cast in the densely populated Tiszaújváros, which made up about 17% of votes in the interim election, and voted heavily for the opposition. In the remaining 83%, Fidesz won a modest majority, handing it the district as a whole.

In general, the precincts were extremely lopsided, with the average margin for the winner in each precinct being over 24%. This means that precincts’ positions on either side of electoral boundaries are extremely consequential. Under the 2010 electoral districts, for example, Tiszaújváros was wholly contained by a much smaller electoral district, making an opposition victory more likely (MSZP won the district in 2006).

Mapping precincts may seem inconsequential, but precinct data can be key to studying electoral trends and electoral systems. In an electoral authoritarian regime like Hungary, the latter is particularly important. More precinct data could help us understand Hungary’s opaque redistricting process and anticipate Fidesz’s electoral strategy. Democracy is about much more than voting, but in a system designed to hide democratic expression in many subtle ways, precinct voting data can be illuminating.

Leave a reply to Joint opposition lists help un-skew the Hungarian electoral system, but they’ll still need a 3% lead to win – Owen Winter Cancel reply