Democrats had a staggeringly positive set of elections on Tuesday 4th November. Zohran Mamdani dominated headlines, defeating former governor Andrew Cuomo to become the New York’s first Muslim mayor and one of the most senior democratic socialists in America. But Dems also dominated elsewhere—in governors’ races in New Jersey and Virginia (as well as those states’ legislatures), statewide races in Pennsylvania and Georgia, special elections in Mississippi, a referendum in California, and local elections elsewhere. Looking through the results, it’s hard to find any bright spots for Republicans.

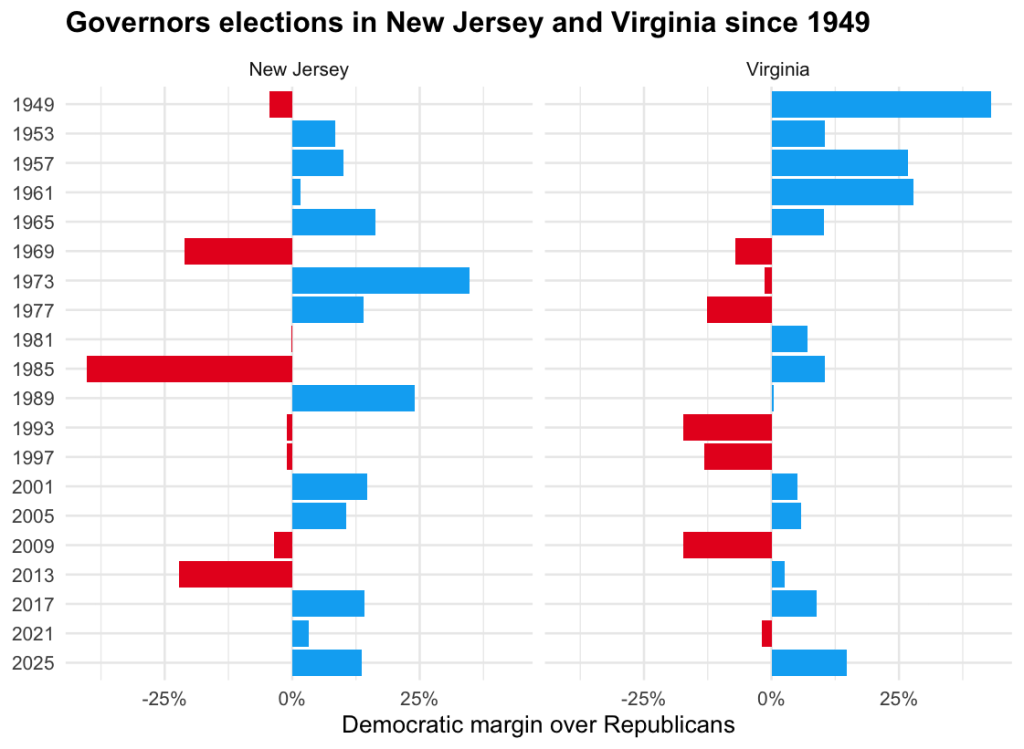

The results reinforce polling which shows that approval of Donald Trump has slumped since the start of his second term, particularly among those voters who swung behind him in 2024 (young and Hispanic voters, in particular). But the question remains whether off-year governors races can tell you anything about parties’ midterm performances. To consider the question, I went back through Virginia and New Jersey’s governor elections since 1949.

Both states have seen competitive governors elections over the past few decades, along with some blowouts. These do seem to have a correlation with the popular vote margin in the following midterms (see chart). The relationship is quite weak, however. It also doesn’t account for the state’s partisan lean (Virginia in particular is much more blue now than it was from 1949-2012), nor the party of the sitting president. It seems from the results that the president’s party tends to do worse in both governors’ elections and midterms, meaning the relationship is not particularly useful.

To get around this, I made a simple model of the governors election, to produce a “performance vs expectation” measure. This model predicted the results in New Jersey and Virginia’s governors election as a function of the incumbent president’s party, incumbent governor’s party, whether the governor was running for reelection or if their party had been in power for at least two terms and the state’s partisan lean versus the country in the last presidential election. Together, these variables had an R squared of only 0.159, suggesting that governors’ elections have been quite unpredictable.

The model expected that Mikie Sherrill in New Jersey and Abigail Spanberger in Virginia would both win by around nine points. The actual margins were 14 and 15 points, meaning Sherrill over-performed by five and Spanberger by six.

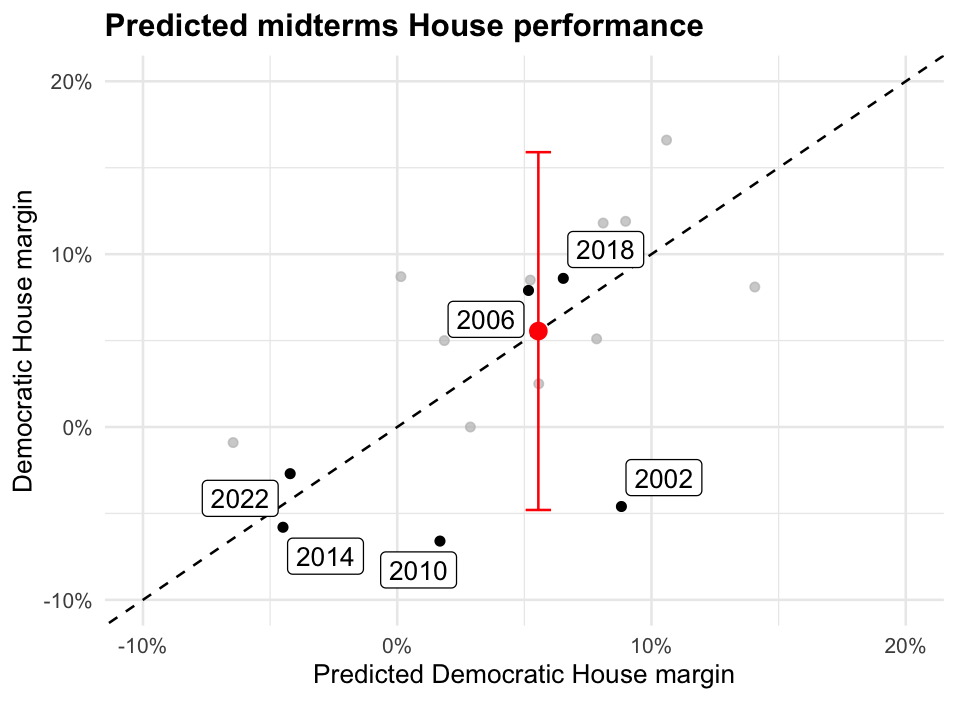

So, how does this compare with midterm results? For this I fitted another simple model with the House popular vote margin predicted by the previous House election result, the incumbent president, and the average Dem over-perfomance in New Jersey and Virginia. As expected, the president’s party was the most predictive variable, worth around 13 percentage points of margin after accounting for the previous result.

The regression suggests that the results in New Jersey and Virginia have a pretty muted predictive power for the midterms. A one point overperformance in Virginia and New Jersey is worth 0.12 points of house margin. With an average overperformance this year of 5.55, the implied effect on the house margin would be 0.71 points, or 1.8 points compared to a scenario where both governors races had been a tie.

Both of the regressions used in this analysis were uncertain and highly dependent on their specification, so a better way of considering the predictive power is to use cross-validation. I reran the whole exercise, holding out one year at a time. The result is a predicted House margin of somewhere between D+16 and R+5, with a central estimate of D+6. Hardly very conclusive.

There’s a chance that governors elections are more predictive in modern elections, when state politics is a closer reflection of the nationwide mood than historically. But with so few elections to consider, the results would not be conclusive.

Even so, you would always rather be the party winning elections than losing them Our expectation of the House popular vote margin should be ~1.8 points higher than had they lost both elections by one vote. In that counterfactual scenario, Democrats would’ve certainly been in a worse situation in the short-term, as panic took over. Perhaps the real benefit of Tuesday’s big victories was narrative. The party has shaken off the post-2024 doom and gloom and can focus on how to beat Republicans in 2026 and 2028.

Leave a comment