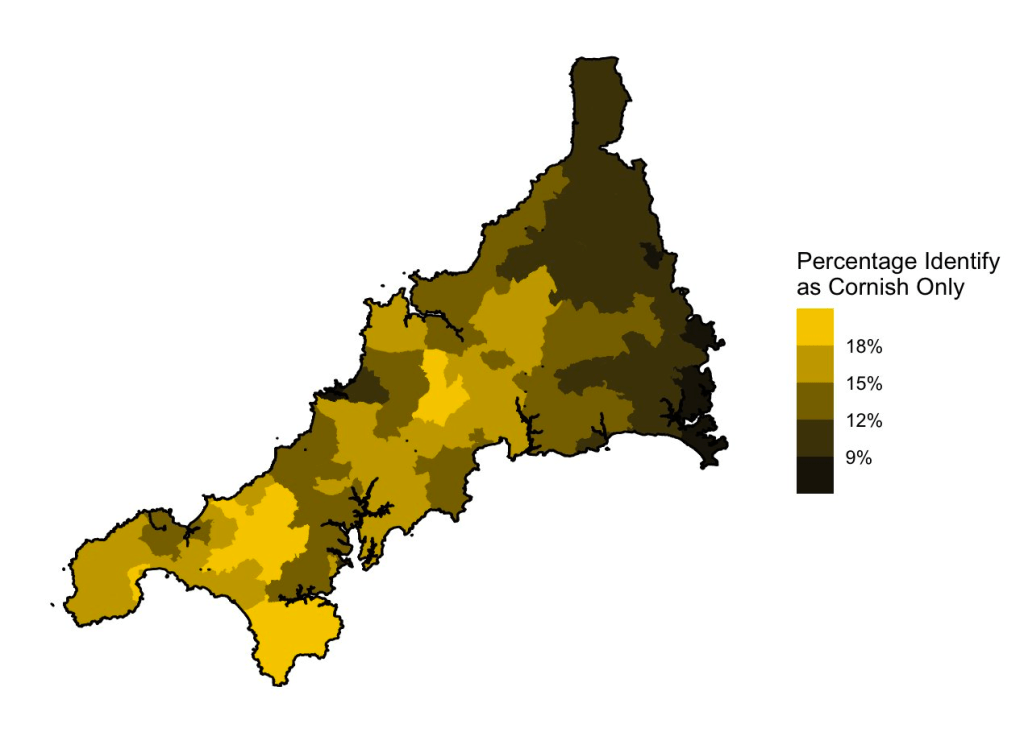

The 2021 Census showed a substantial increase in the number of people who identified as “Cornish” as their national identity. Despite no tick-box option, over 100,000 people in England and Wales wrote Cornish into the national identity question. The data comes seven years after Cornish was recognised as a national minority by the Council of Europe. Despite this recognition, there is little research into Cornwall’s electoral politics and public opinion. And with six Conservative MPs elected in 2019 – much like most of rural southern England – is Cornwall really politically distinct?

To test this question, I looked at British Election Study data from June 2020. This wave of the BES included almost 32,000 respondents, 393 of whom lived in Cornwall. 393 is too small a sample size to find accurate point estimates of opinion, but by incorporating data on respondents’ characteristics we can begin to test for a causal effect of Cornish residence. To do this, I use a method called Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM).

CEM works by finding ‘matching’ data points from two groups to estimate the causal effect of an independent variable. In this case, for example, I took residents of Cornwall and matched them with residents of other English counties who had the same age, education level, rural/urban neighbourhood, housing tenure, personal income, ethnicity, work status and gender. By comparing ‘matching’ respondents, you can see the difference between Cornwall and the rest of England, while controlling for difference between individuals.

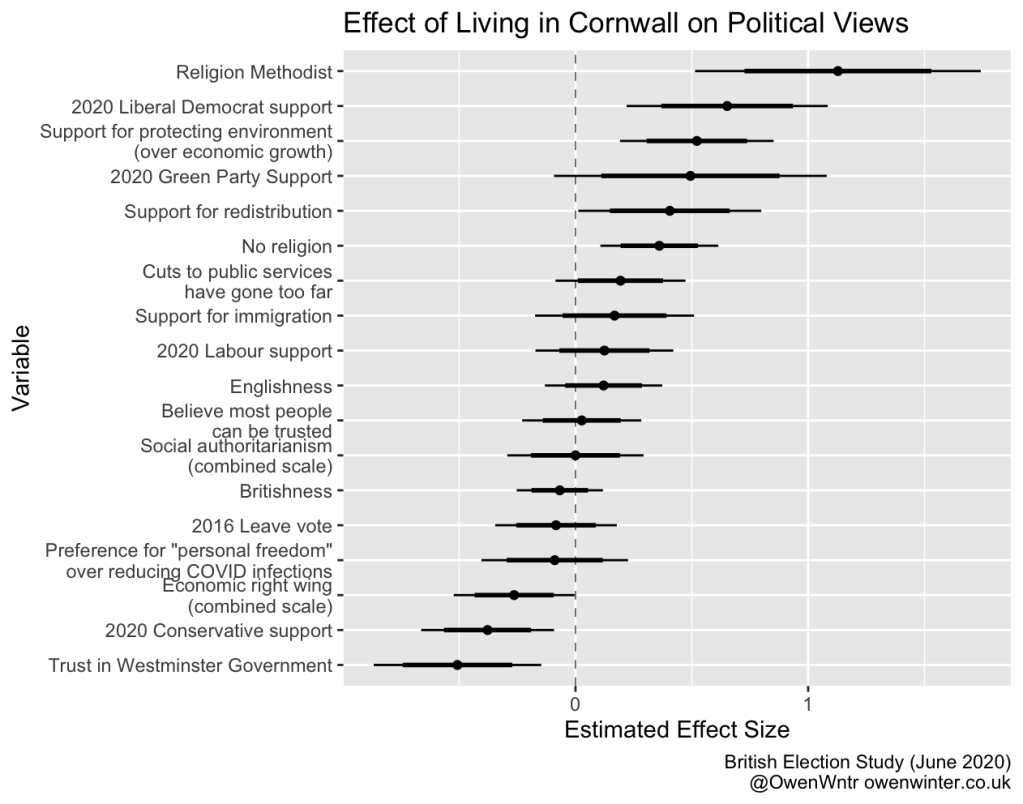

I tested the effect of living in Cornwall for each of 18 variables, including voting intention, religion, opinions on political issues, and BES ‘values’ scales. The results are plotted below. 8 of the variables show a ‘Cornish effect’ outside the 95% confidence interval.

The most substantial estimated effect, by far, is on identifying as a Methodist. This follows a long history of Methodism in Cornwall, with Methodist founder John Wesley visiting the county 33 times between 1743 and 1791. In the 19th century, Methodism was predominant in Cornwall and more popular than anywhere else in England. Although Methodism is a minority denomination in Cornwall today, its historical legacy likely continues to play a role in religious and political affiliation. For example, Cornwall also has a disproportionate number of respondents who identify as having ‘no religion’ – perhaps due to more rapid secularisation among Methodists than other denominations. In that sense, it is difficult to say whether religious identity is a cause or effect of distinctive Cornish political identity.

After Methodism, the most substantial effect is on support for the Liberal Democrats. Although the Liberal Democrats have declined rapidly in Cornwall since 2010, falling from 42% of the vote to 22% in 2015, 24% in 2017 and 19% in 2019, their support is far higher than you would expect given Cornwall’s demographic characteristics. Again, this has a historical component, with a long Liberal Party tradition in Cornwall, closely linked to Methodism. More recently, Cornwall elected at least one Liberal or Liberal Democrat MP at every election between 1964 and 2015, including prominent names such as David Penhaligon. Clearly, some combination of political ‘culture’ and Liberal Democrat campaigning continues to lend itself to a Cornish Liberal tradition.

One common explanation for Liberal Democrat success in Cornwall is a theorised anti-establishment sentiment in the county, perhaps owing to distance from Westminster and perceived neglect from the two major parties. The BES data gives some credence to this idea, with trust in “the government in Westminster” being disproportionately low among Cornish respondents. This question is hard to separate from support for the Conservative party – in government at the time of the survey – which is also unusually low in Cornwall. There is no negative effect found for the Labour Party.

Other political attitudes with a substantial “Cornish effect” include support for protecting the environment (and, in turn, support for the Green Party) and support for economic redistribution by the government. In terms of “values”, Cornish respondents score as significantly less economically right-wing than expected. These figures are at odds with Cornwall’s typical political reputation, and its current Parliamentary representation, but show a county with a streak of economic populism and environmentalism above what would be expected from comparable voters elsewhere.

Here, it is important to note the areas where there is no significant ‘Cornish effect’. Most surprisingly, the BES data indicates no substantial effect on English or British national identity. This runs counter to the Census 2021 data and suggests that Cornish identity is held alongside English or British identity, rather than in their place. There also appears to be no effect on social liberalism, attitudes to immigration, support for leaving the European Union, views on COVID restrictions or broader social trust. These are interesting especially for how they interact with variables where a significant effect is found. Increased support for redistribution is not driven by high social trust, for example. Disproportionate support for the Liberal Democrats in Cornwall is not driven by social liberalism or support for the European Union.

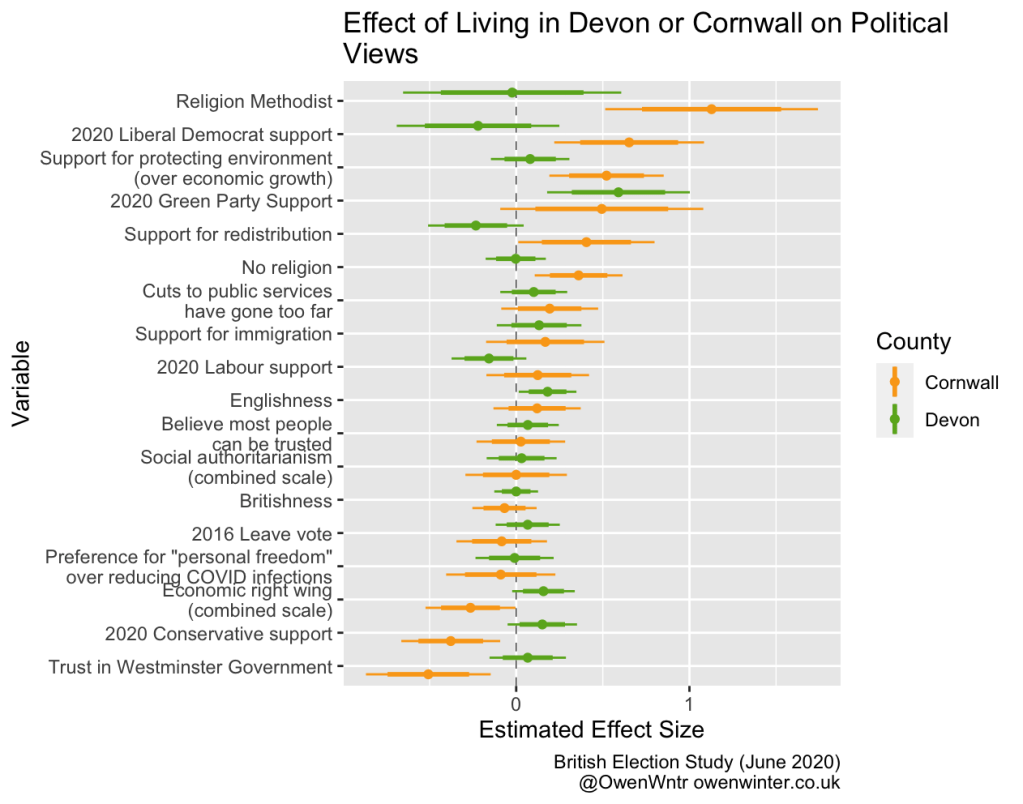

Another key question is whether these Cornish effects are truly distinctive, when compared to other counties. It may be that all counties, or any arbitrary geographic groups, have comparable localised effects. To test this, where better to look than across the Tamar? I re-ran the tests using respondents from Devon (N=784) and compared the results:

The plot above shows how fewer variables have a pronounced county effect in Devon than Cornwall. The biggest divergence is on Methodism, which is predictable. After that, the greatest difference is the effect on the Liberal Democrats. This is more surprising, given substantial Lib Dem support in Devon in the past. On political attitudes, Devon has the opposite effect to Cornwall on support for redistribution, trust in Westminster, and right-wing economic values. While Cornwall has a distinctive left-wing skew on economic issues, Devon leans further to the right.

This difference is difficult to explain. A historicist explanation might focus on the distinct traditions of Methodism versus the Church of England, or the extension of the manorial farming system in Devon but not Cornwall. A more recent explanation might focus on the effect of mining, in a similar vain to the political histories of mining communities in Wales, Scotland and the north of England. Or the explanation might be entirely modern, caused by Cornwall’s relative deprivation, Devon’s greater economic diversity and prosperity, or Devon’s strong connection to the Royal Navy.

Cornwall has the larger estimated effect on 13 of the 18 issues surveyed (although Methodism was selected based on a prior expectation). Of the final five, Devon has a more pronounced positive effect on support for the Green Party and a positive effect on English identity, while the other effects are within the margin of error. Interestingly, there is no positive correlation between Cornwall and Devon’s county effects (if anything the correlation is slightly negative). This is significant because it undermines the idea of a broader “South West”, “Westcountry” or “Devon and Cornwall” political distinction.

The survey data here gives some tentative support to the idea of distinctive Cornish political values, when demographic variables are held constant. Comparison with Devon suggests a substantial difference between neighbouring counties and more pronounced effect sizes for Cornwall. As Cornish identification grows, it will be interesting to see whether a more pronounced political Cornishness develops.

Leave a comment