Since 2016, EU Referendum vote has been highly predictive of voting behaviour. It is well established that the Conservatives won many leave-voting Labour supporters at the 2019 election, helping to secure a huge majority. Meanwhile, Labour and the Liberal Democrats fared comparatively better in Remain-voting areas.

Generally, this discussion focusses on partisan defections ’caused by’ Brexit preferences. By looking at individual-level longitudinal data, however, we can also see a parallel effect. Voters also bring their Brexit preferences into line with their party loyalty. Using British Election Study data, we can look at voters by their 2015 vote, before the effects of Brexit on party support were as decisive.

Excluding ‘Don’t Know’, 29% of Remain voters who voted Conservative in 2015 now support Leave. This compares to only 6% of Remain voters who voted Liberal Democrat and 5% who voted Labour. On the other side, 24% of Leave voters who voted Labour in 2015 and 18% who voted Liberal Democrat now support Remain. This compares with only 8% of those who voted Conservative in 2015.

The effect here is clear. After the Referendum, as the Conservative Party swung behind Brexit, they brought their voters with them. Meanwhile, as Labour and the Liberal Democrats became increasingly opposed to Brexit, their voters followed, too. This happened in parallel to Remain and Leave voters moving to support parties that matched their Brexit preference.

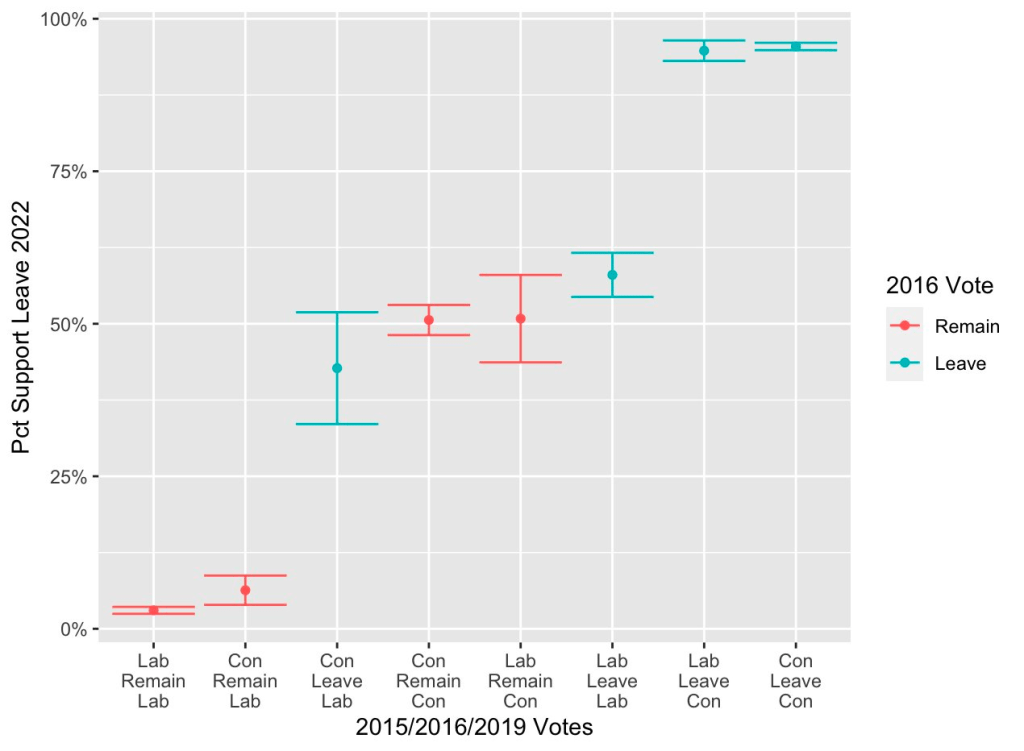

The plot below combines these effects by looking at respondent’s 2015, 2016 Referendum and 2019 votes, between Labour and the Conservatives. It shows how extremely few committed Conservative voters have switched from Leave to Remain, while extremely few committed Labour supporters have switched the other way. The next most committed groups (on Brexit) are those which changed parties – Labour-Leave defectors to the Conservatives still support Brexit, while Conservative-Remain defectors to Labour still oppose it.

The only groups for which there are significant changes in opinion on Brexit are those which having mismatched parties/Brexit preference. Conservatives who voted Leave but switched to Labour now narrowly support Remain, bringing their Brexit preference into line with their new party. Around half of Labour-Remain voters who moved to the Conservatives have also switched, in line with their new party. Meanwhile the uncomfortable Con-Remain-Con and Lab-Leave-Lab voters are split 50-50 in 2022, moving towards their party’s positions.

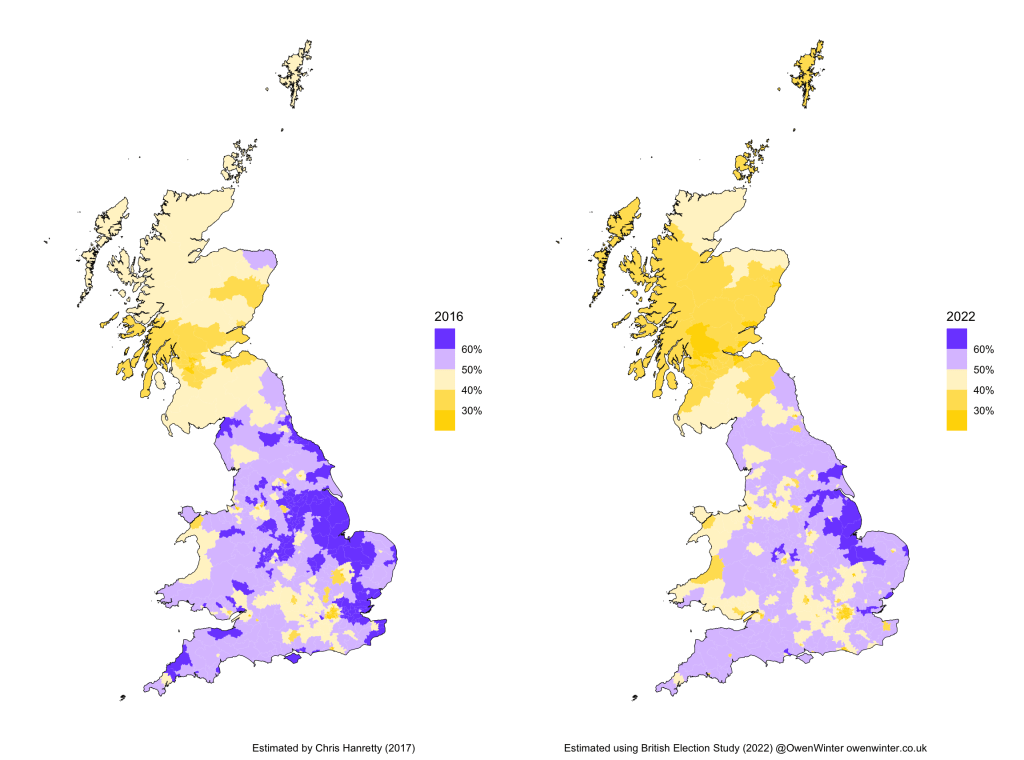

This likely has an effect on the geography of Brexit. Below I use MRP to estimate EU Referendum voting intention in May 2022. On the left, we see Chris Hanretty’s (2017) estimated Brexit support by constituency while on the right is my May 2022 estimates.

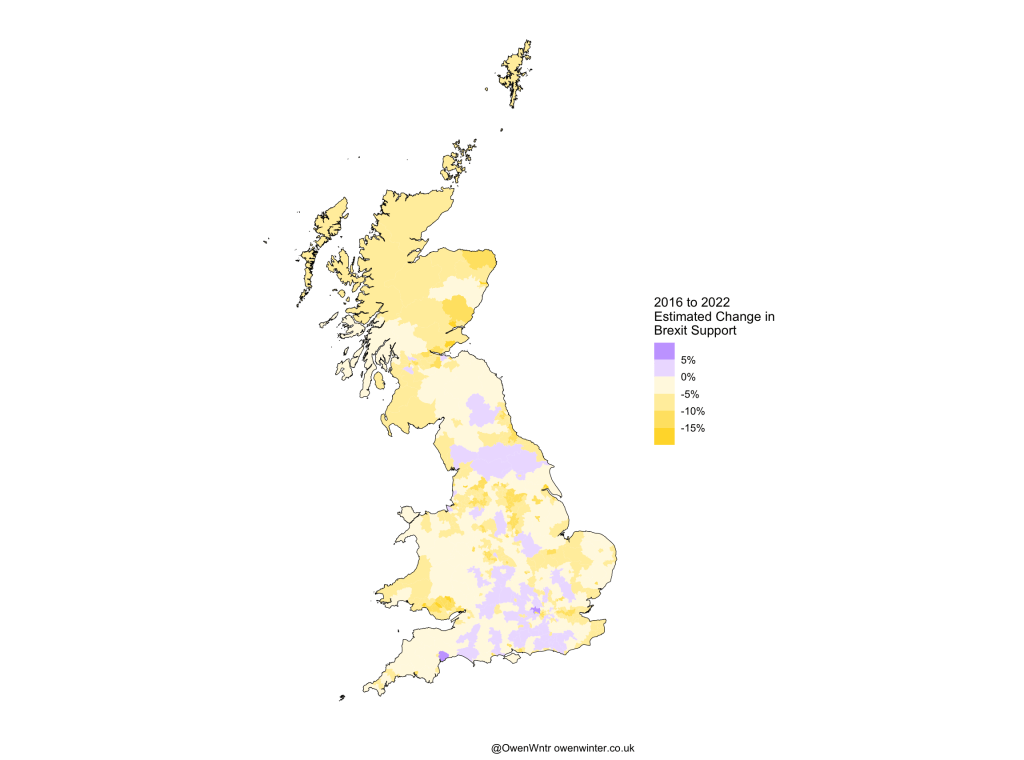

Support for Brexit has dropped almost across the board, but we can clearly see huge swings in SNP-voting Scotland (further in favour of Remain), Labour and Plaid-voting Wales, and Labour heartlands in the North of England. Support for Brexit, meanwhile, stays fairly steady in Conservative seats. The estimated change in support is mapped below.

The model used to estimate these effects shows a strong effect of 2019 Conservative vote, positively associated with 2022 Leave support, and a negative effect for Labour, SNP, Liberal Democrat or Plaid vote, even once you control for 2016 Referendum vote.

This should subtly change how we think about the effects of Brexit on politics. The risks for Labour of inadequate support for Brexit are lower, as its voters move into line with party policy. Many Labour seats in the North of England had huge Brexit votes which have now been reversed or significantly decreased. Meanwhile, for the Conservatives, the risks in Remain-voting areas are also less significant. It is likely that most 2015 Remain-Conservatives have their already left for the Liberal Democrats, or now support the party’s Leave position. Brexit support continues to shape politics, but the effect on electoral geography will be dampened by the fact that voters have sorted themselves by party, as well as by Brexit preference.

Note: One significant caveat for this analysis is that it uses May 2022 data. Since May, it seems the pendulum has swung even further against Brexit. This process is also likely to be shaped by party preferences, but the data is not available for analysis of the same granularity.

Leave a comment