My contribution to the Young Fabians Environment Network pamphlet ‘Ways to Save the World’ the full pamphlet can be found here.

Until recently, interest in electoral reform was reserved for political anoraks. Around election time, some party activists grumbled about the unfairness of the system, but there were few serious attempts to change it. In that sense, 2015 is the year when electoral reform went mainstream.

The 2015 General Election was the most disproportionate in British history. Three parties – UKIP, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens – received 24.5% of the vote but won only 1.5% of MPs. Meanwhile, the SNP won 56 MPs with less than 5% of votes. Millions of people felt unrepresented, and over half a million signed petitions calling for a voting system which ensures that seats match votes. In the aftermath of the election, Make Votes Matter formed to campaign single-mindedly for Proportional Representation (PR) in the House of Commons.

PR, put simply, is any system of electing MPs which ensures that votes broadly match seats. Under PR, if a political party gets 10% of votes, they should get approximately 10% of seats. This stands in stark contrast to the current First Past the Post (FPTP) system, in which each local area has a single MP but representation in Parliament is not closely linked to popular support.

So, what does this have to do with climate policy?

How our political system entrenches climate change

Since 2015, Make Votes Matter has expanded hugely, encompassing thousands of activists. It has committed itself to ensuring that PR is not a fringe issue, or one which interests only the politically engaged. To this end, it has drawn on the work of academics to argue that the electoral system has a huge impact on policy outcomes – linking PR to so-called ‘bread-and-butter’ issues. The campaign argues that switching to PR is key to taking action on crucial issues – including the climate crisis.

It is a bold claim, that PR would help us tackle climate change, but it is gaining traction amongst electoral reformers, backed up by political scientists. By looking at evidence from around the world, we can paint a picture of the radically different policies that voting systems produce.

Salomon Orellana (1) of the University of Michigan compared ‘proportionality’ (how closely seats match votes) with the percentage change in CO2 emissions per capita between 1990 and 2007. He found that countries with a pure PR system could expect to have their percentage change in CO2 emissions decrease by 11% more than countries with voting systems like the UK’s. He also looked at the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), an independent scorecard which ranks countries on 24 indicators across ten issue categories covering environmental health and ecosystem vitality, and found that PR countries could expect a 4.5% higher EPI score. Similarly, University of California’s Arend Lijphart found that ‘consensus democracies’ – of which PR is a key feature – have on average 6% higher EPI scores than ‘majoritarian’ democracies (2).

Economist Vincenzo Verardi takes a different approach, looking at international agreements to tackle climate change (3). He found that even when controlling for regime type, economic development and geographic region, countries which use PR are significantly more likely to be members of intergovernmental environmental organisations and treaties.

There is clear evidence of a correlation between a more proportional electoral system and better performance on climate issues – even when taking other variables into consideration. So what is driving this relationship?

One key factor in climate policy is thinking in the long-term. Because the effects of climate change may not be fully felt until it is too late, taking a long-term approach is vital. PR voting systems allow politicians to take this long-term view, rather than forcing through legislation along partisan lines and rapidly changing policy directions.

Lijphart argues that whilst single-party majority government leads to ‘fast’ decision making, this does not lead to ‘wise’ policies (4). Without proper debate, countries with single-party governments tend to have poorly thought-through policies which frequently have to be reversed, because they have not been subject to proper scrutiny. LSE’s Patrick Dunleavy argues that this is exactly what happens in the UK, with politicians more interested in supporting their party than properly scrutinising legislation (5). He argues that FPTP produces politicians who are incentivised to score points and governments that can dominate the legislature, rather than engage constructively with policy-making.

Building coalitions for sustainability

Coalitions can also make policy-making more consistent between different governments. In two-party systems the alternation of governments leads to frequent changes in policy direction. Once in power, single parties can easily reverse the policies of the previous government, leading to sharp changes in direction. Under PR, by contrast, policies must be backed by parties that around 50% of the population voted for (6), allowing them to be more deeply embedded and harder to reverse. A more consensual political system, using PR, means policies are more successful in the long-term. This means more sustained action on issues such as environmental regulation or biodiversity, where long-termism is key.

Finland, for example, has had uninterrupted multi-party government since 1972, with its PR system ensuring that parties have to work together to form a government. There, a number of innovative methods have been adopted to ensure long-termism: a termly ‘Government Report on the Future’, which is debated publicly; the government-funded Finnish Environment institute; a national panel on climate change, comprised of independent experts; and the unique Parliamentary Committee on the Future.

Some political scientists go further, arguing that proportional electoral systems are better at representing climate issues in particular. Climate action can be categorised as being backed by ‘diffuse interests’ – with a large and disparate number of benefactors and contributors. The opponents of green policies, on the other hand, tend to be concentrated into particular groups, such as certain environmentally harmful industries or specific local areas. Because proportional electoral systems tend to lead to governments supported by a greater share of voters and political parties, policies which have broader support are more likely to be adopted than those which satisfy special interests. On the other hand, under FPTP with single-member districts, legislators are more likely to feel the pressures of lobbyists and ‘pork barrel politics’.

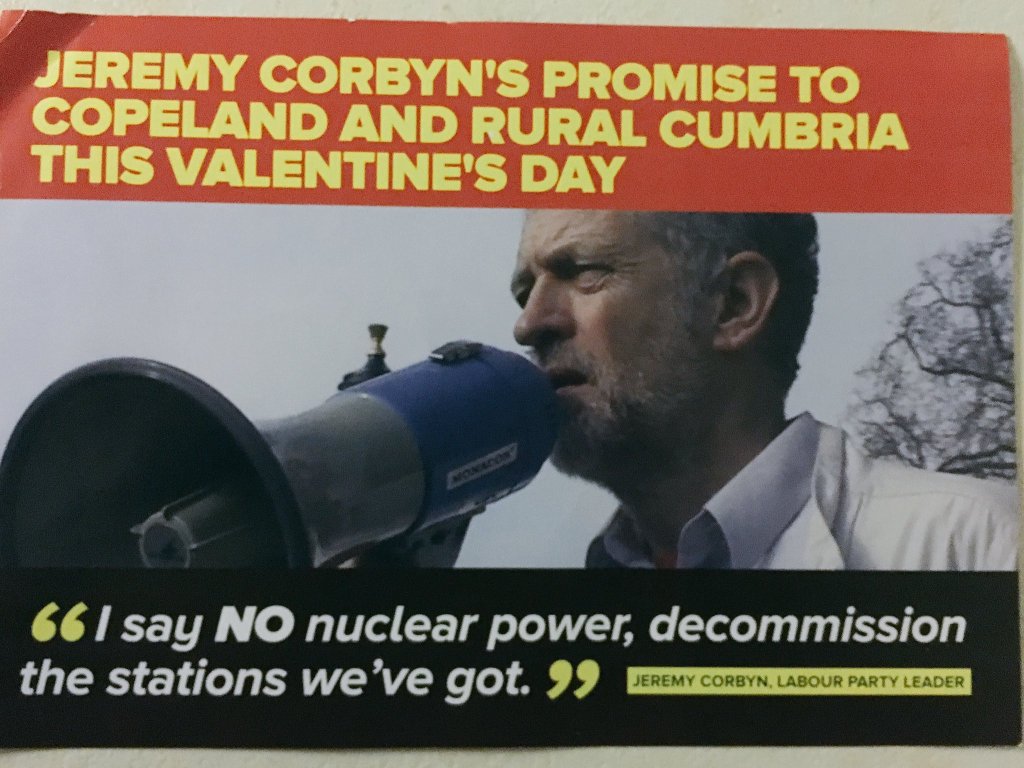

To put this into practice, consider MPs in the UK. Many MPs represent constituencies which include major employers in environmentally harmful industries. From an electoral perspective, these MPs are incentivised to support policies which protect these industries. Take the 2017 by-election in Copeland, triggered by the resignation of the local Labour MP. During the campaign, Conservative leaflets hammered Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn for being opposed to new nuclear power plants, because Copeland is heavily reliant on the nuclear industry. Whilst building new nuclear power plants may or may not be the right thing to do nationwide, opposition or perceived opposition to nuclear power can impose a heavy electoral cost at a local level. Labour learnt this lesson the hard way, with the Conservatives winning the seat.

Promoting a diversity of voices for climate action

Across the UK as a whole, or any country, the majority of people would benefit from taking action on climate change. However, because the supporters of environmental policies are diffuse whilst the opponents are concentrated, there are many more constituencies where opposing environmental protection is a critical electoral issue, meaning more MPs with an incentive to oppose. Multi-member districts under PR mean a broader range of interests represented in the constituency, rather than candidates solely chasing the small number of swing voters who could win them the seat.

Political parties are acutely aware of this. By following the same logic as above, on a national scale, there are far more votes to be won in ‘marginal’ seats by pursuing policies which support local interests, even if those are damaging for the environment.

Of course, under any political system, climate action depends on public support, but there is also evidence that electoral systems can influence public attitudes. Far from solely being a way of choosing MPs, Orellana argues that electoral systems alter the flow of political information and can therefore influence public attitudes (7). He finds that countries with purely proportional systems could expect to have 9% higher support for environmental protections than those which use FPTP.

Proportional electoral systems lead to a broader range of parties contesting elections, leading to a broader political discourse. This allows controversial issues and policies to be put forward, becoming mainstream earlier than in countries with strict two-party systems. Although environmental protection tends to be well-supported in principle, expensive policies which will actually tackle the climate crisis are much harder to suggest.

Orellana points to the United States as an example. Democrats and Republicans frequently accuse each other of planning to raise taxes on gasoline, attacking the proposal despite the environmental cost of car use. Raising the gas tax is too controversial for either party to support. Whilst there is no third party to argue the case for higher gas tax, the elite consensus reinforces public opinion and no alternative is discussed. The two main parties in the USA restrict political information and prevent public acceptance of the cost of protecting the environment.

Whilst in every country environmental movements have to fight for climate action, the evidence shows that climate activists under PR can expect to have more success than those under FPTP. That is why Extinction Rebellion has put democracy at the heart of its demands for climate action, pushing for a Citizen’s Assembly to side-step our unrepresentative political institutions. It is also why Friends of the Earth and environmental activists George Monbiot and Jonathan Porritt have joined Make Votes Matter’s Alliance for PR.

To produce the transformative action needed to solve the climate crisis, we need political institutions that can bear the strain. For that reason, Proportional Representation is crucial.

(1) Salomon Orellana, “How Electoral Systems Can Influence Policy Innovation”, Policy Studies Journal, Vol.38(4), (October 2010): 613-628. (2) Arend Lijphart, Patterns of democracy: government forms and performance in thirty-six countries, 2nd ed, New Haven: Yale University Press, (July 2012) (3) Vincenzo Verardi, “Comparative Politics and Environmental Commitments” (December 2004) (4) Arend Lijphart, Patterns of democracy: government forms and performance in thirty-six countries, 2nd ed, New Haven: Yale University Press, (July 2012) (5) Patrick Dunleavy, “Policy Disasters: Explaining the UK’s Record”, Public Policy and Administration, Vol.10(2), (June 1995) 52–70 (6) Markus Crepaz, “Constitutional structures and regime performance in 18 industrialized democracies: A test of Olson’s hypothesis”. European Journal of Political Research, Vol.29, (January 1996) 87-104. (7) Salomon Orellana, “How Electoral Systems Can Influence Policy Innovation”, Policy Studies Journal, Vol.38(4), (October 2010): 613-628.

Leave a comment